공지사항

교사세미나 안내 (6/9,서울)

4차 산업혁명시대, 교육패러다임이 바뀐다!

21세기 핵심역량을 키우는 리딩교수법 세미나에

교사 여러분을 초대합니다. (선착순 마감)

자세히 보기 >>

4차 산업혁명시대, 교육패러다임이 바뀐다!

21세기 핵심역량을 키우는 리딩교수법 세미나에

교사 여러분을 초대합니다. (선착순 마감)

자세히 보기 >>

| Learning to Love Reading, Part 1 |

|---|

|

file|

2021.03.08

|

|

by Jon Edwards

Why do so many students hate reading? Parents and teachers would love to see every student get excited about books and be self-motivated about reading. But, for a lot of students, sitting down to read a book seems to be about as much fun as sitting down in a dentist’s chair! Reading probably doesn’t appeal to many students because—let’s face it—other forms of entertainment, like movies, computer games, or online videos, offer a clearer and more attractive “trade-off”: a minimal investment of time and effort for a lot of excitement. So, it’s no wonder that the majority of students might find reading a book—whether in their mother tongue or in English—far from enjoyable.

How do we help students have that critical first positive experience that’s going to prove to them that reading can actually be rewarding? Obviously, this is a complicated issue. In this series of blog posts, I’d like to look at some of the things we can do as teachers to help students learn to love reading.

Part 1: Boosting Vocabulary Skills  One of the biggest barriers to enjoying reading is unfamiliar vocabulary. The more unknown words and phrases students encounter within a passage, the more they will struggle to understand it. There are some things we can do to mitigate this frustration. We can provide reading material that is appropriate for students’ language level (using leveled readers and tools that measure the readability of a text, for example). We can also sometimes predict vocabulary in a passage that will pose a challenge and provide support by explaining it in advance or by providing a glossary that students can refer to.

However, it is neither possible nor desirable to always present students with reading material in which all vocabulary is familiar to them. Encountering unfamiliar vocabulary is inevitable, and it is necessary for students to develop their language skills and to become independent learners. In fact, a critical language skill is being able to “gloss” the approximate meaning of an unfamiliar word closely enough that it doesn’t interfere with the overall understanding of a passage.

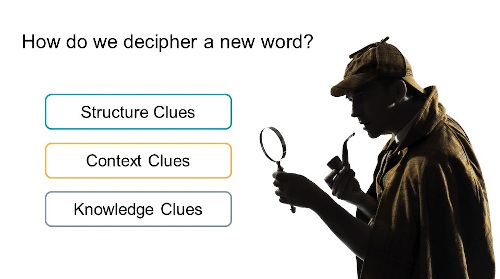

When you’re reading and encounter a word you don’t know, how do you go about deciphering its meaning? You probably don’t refer to a dictionary. (Doing so for every unfamiliar word would make reading an arduous task.) If you’re like most people, you probably make an approximate guess at the meaning of the word by subconsciously gathering various clues.Here are some of the most important clues we use to work out the meaning of unfamiliar words.

1. Structure Clues

a. Part of Speech

If we know the part of speech of an unknown word, we already know some general things about its meaning. For instance, if it is a noun, it’s a person, place, thing, or idea. If it’s a verb, it’s probably an action. If it’s an adjective, it’s a quality or characteristic; and if it’s an adverb it could be a way of doing something. Consider the following example: “The cat lay on the floor, purring contentedly in the sun.” In this sentence, “contentedly” is a way that happy cats purr. We can put this together with other kinds of clues to get a fuller sense of the meaning.

b. Agents, Recipients of Action, Objects, Referents, etc.

The relationships between words can give us different kinds of clues. For example, if we know the agents of an action, or the recipients or objects of an action, that can tell us something about the action, and vice versa. For example, in the sentence, “Each summer, thousands of tourists flock to the beaches of Cape Cod,” we can determine that it is tourists who are flocking and that they are flocking to beaches. So, we might reasonably conclude that ‘flock’ means something like ‘travel’ or ‘go’.

c. Word Structure

In many words, the morphology, or structure, of the word can give us clues about its meaning. This is especially true of latinate words (those that derive from Latin), which are constructed of prefixes, roots, and suffixes. But with other kinds of words, as well, we can get information about the meaning from the structure. We can look for the following, any of which could provide clues from which to deduce the meaning:

- affixations (ex., unhappy, clueless);

- compounding (ex., thunderstorm);

- conversions (ex., cook a meal, a cook);

- derivations (ex., excite, exciting, excitement).

Based on knowledge of its structure, the meaning of a word can be worked out, at least in a vague way.

2. Context Clues

a. Direct Definition / Description

Sometimes, a very uncommon word may simply be defined by the author, as in the following example: “It was an idyllic day—warm and sunny—a perfect day to go to the beach.” Here, the description can help to explain what is meant by the word “idyllic.” Commas, dashes, or expressions like “that is to say” can indicate where direct definitions or descriptions are being provided.

b.Synonym

A word with the same meaning or a similar meaning may appear nearby an unfamiliar word in the text. Writers often use several different words for the same thing within a passage to avoid repeating the same word. Consider the following example. “A beaver's incisors continue to grow throughout its life. They use these sharp front teeth to cut into hard trees, so they are always being worn down.” We can see in this excerpt how the writer is using “sharp front teeth” as a synonym for “incisors”.

c. Example

Sometimes, a passage may provide one or more items as examples of a category. The examples can help to explain the category if it is an unknown word; or the category may help to explain one or more of the examples. Examples are usually introduced with “like,” “such as,” “including,” or “for example.” Consider the following sentence. “Celestial bodies, including the sun, moon, and stars, have been thought to foretell the events.” Based on the examples, we can tell that “celestial bodies” are things that are in the sky.

d. Antonym / Contrast

A text may present a contrasting idea or give a word with an opposite meaning, which can help to explain the meaning of an unfamiliar word. Words like

“although,” “however,” “where as,” and “but” may signal an antonym or contrast clues, as in the following sentence. “When a mammal’s body is cold, the blood vessels near the surface of the skin tighten and contract; whereas, when it is warm, they dilate.” Here, dilate may be an unfamiliar word, but its meaning is clarified by the contrast with “tighten and contract” earlier in the sentence.

e. Mood / Tone

Sometimes, the overall feeling, mood, or tone of a passage or sentence can give a general sense of the meaning of the word as it usually should fit the mood or tone. Based on the mood or tone of the following sentence, we can probably understand, at least generally, the meaning of the words “ecstatic” and “boisterous.” “Bursting into the room filled with balloons, presents, and party decorations, the children were ecstatic and boisterous as they took their seats.”

f. Cause and Effect

A text may present the cause or effects of a situation or action, which can provide clues to the meaning of a word. Take the following, for example. “The dog wouldn’t have got out of the house if the door hadn’t been left ajar.” We can deduce the basic meaning of the word “ajar” based on the fact that the dog got out of the house; the door obviously must have been open somehow. Words like “because,” “since,” “therefore,” “thus,” “so,” etc. show that these kinds of context clues are available.

3. Knowledge Clues

a. Personal Experience / Common Sense

Based on their own experience or shared cultural knowledge, students can deduce the meaning of unfamiliar words. For example, look at the following sentence. “She put on her coat and shoes and, glancing at herself in the mirror, walked out the door.” The exact meaning of the word “glance” might not be clear, but we can get a sense of it based on similar experiences in daily life.

b. Background Knowledge

The reader may know enough about a topic to figure out the general meaning of a new term. Helping students to recall this background knowledge with a short lead-in to a reading passage can help more easily make sense of any unfamiliar words in the passage.

To help students enjoy reading more, it’s important to help them develop these vocabulary skills. You can either teach them systematically by focusing some class time on them one by one, or you can look for opportunities to have students practice them more on an ad hoc basis. For example, when they ask questions about vocabulary in a passage, you can ask them questions to guide them through the “clue-gathering” process. Whichever way you choose, boosting students' ability to be “word detectives” and figure out the meaning of unfamiliar words using these clues will make it more likely that they’ll find reading enjoyable.

|

4차 산업혁명시대, 교육패러다임이 바뀐다!

21세기 핵심역량을 키우는 리딩교수법 세미나에

교사 여러분을 초대합니다. (선착순 마감)

자세히 보기 >>